Grief, Embodiment, & The Pandemic

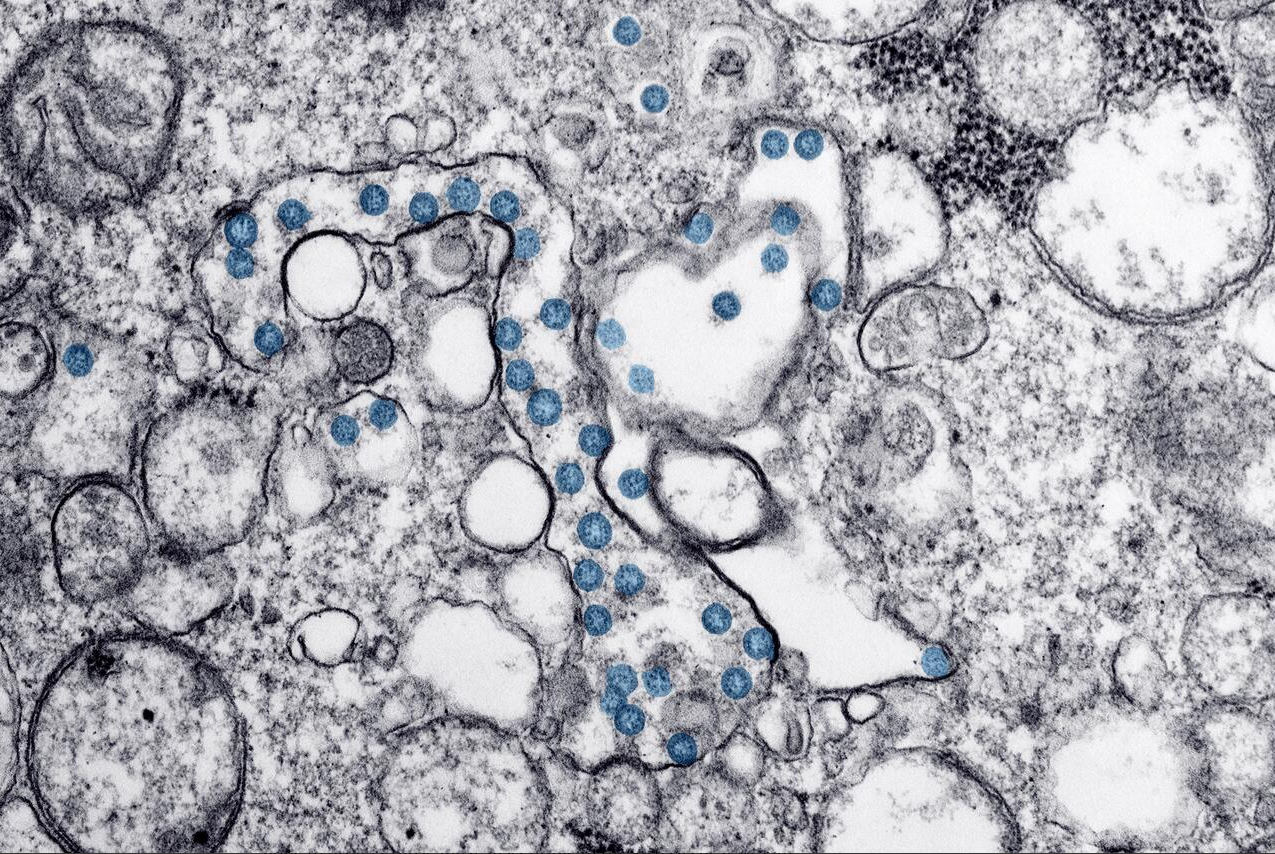

Microscopic Image of Coronavirus isolate. © CDC/ Hannah A Bullock; Azaibi Tamin

It stopped me from scrolling and held my attention longer than anything else on the internet that day. I found myself meditating on a microscopic image of a Coronavirus isolate. I sat at my computer, leaned back, cross-legged, breathing directly into the terror this tiny yet powerful infectious agent was spreading across the planet. Tiny blue dots swimming in between swirling lines and circles, a galaxy of fuzzy viral particles. It was beautiful, quite honestly. And there I sat, feeling my aching heart, my shallow breath, my buzzing body. There I was alone, a bit of the masochist I am, staring straight ahead into my fear.

Just two days before Covid-19 changed our way of life, my partner told me he no longer wanted to be in a committed relationship and that he wanted to move out. It was sudden and somehow final. Breathe. He left to stay with friends. I stayed in our house, barely able to move, eat, or sleep, crying relentlessly. A few days later the Mayor issued a social distancing order, my partner came by to get his things and we embraced in one last tearful, shaky good-bye. One last hug; from anyone, for a long time.

As the pandemic began to spread throughout the U.S. my mind got busy trying to protect itself from feeling the terror my body already sensed. Still barely eating, sleeping or moving, I started to brainstorm all the zoom calls, webinars, and web content I could host to help others in every way I knew possible. As a somatic sex educator, whose work is trauma-informed and pleasure-centered, I figured I was built for this pandemic. I believed I knew just how to help everyone find pleasure in even the hardest of times.

Thank God my body had a different idea. My grief, the world’s grief, my break up, the pandemic, all mixed up in my body with nothing else to do but feel it. Perhaps a different kind of erotic experience; afterall, pain can be a wonderful sensation on the pleasure spectrum. I dragged my body from couch to bed to floor to bed to bath to couch and bed again. I cried for several hours each day. I had lost the person I thought I would marry and I would be facing the uncertain future of a global pandemic alone. Breathe.

An old college friend who had the virus, is immune-compromised, and has since recovered, describes over two weeks of hell, “every single system in my body feels taxed...I don’t need advice or resources at this time - I have everything I need.”

I didn’t have the virus but she describes my experience exactly.

As I write this I feel guilt and shame. How could I compare my experience of heart break to someone who is ill from a virus that is killing hundreds of thousands across the planet? Breathe. Then it hits me. How could I not? This is being human. I am having a human experience of suffering and I am relating to other human experiences of suffering. There is no trauma award here - no one’s suffering is more or less than another. And feeling shame and guilt are all an appropriate response to grief.

So I typed into google: “Can you die from…” the sentence stem suggests: “from a broken heart?” or “the flu?”.There were times in those weeks when death seemed like a more compassionate option than the suffering I was enduring. The first two weeks of my break up I soaked the sheets in sweat and nightmares. Every few days I was sure I had contracted the virus because my symptoms were so similar. I was exhausted all of the time. Except for when I was angry - then I moved excessively. My ears and throat burned, my chest lived with a heavy weight on it and my lungs contracted. I would cough in moments of severe distress.

In Traditional Chinese Medicine, grief is associated with the lungs. Breathing and bowel disorders are rooted in excess grief and sadness, and the inability to fully express these feelings. Here come those big sighs, a release valve the body uses to regulate itself. Expressing grief however it wants to come out is healthy for the body, and keeps the lungs free to do their job: breathe.

I could sense the collective grief yet to come and I was ready to catch it like a midwife in labor. I was eager to see the latest death toll: the frenzy and the fear matched the state of my nervous system. I was not afraid, so I thought - perhaps this was part of the denial phase? We were being braced for two weeks of tremendous loss as the pandemic was predicted to hit its peak in the U.S., and somehow it was comforting to sense something bigger affecting all of us, collectively. Suddenly I wasn’t alone in my distress. Others were grieving too: loss of jobs, weddings, book launches, graduations, pilgrimages, birthdays, toilet paper, hand sanitizer, savings, stability, safe housing.

I had become a grief warrior, ready to tackle it, and still naive to think I was ready to hold the grief of others. But again, my body couldn’t lie. It could not hold space for others. It would have to pause and excuse myself to another room and cry. My body sought to do less. It called for walks near the river and bayou, extra slow bike rides, and tremendous stillness. It sought to take the pressure off of working, cleaning or doing anything other than the next right thing. All I could do was feel my loss, our collective loss, my heart in pieces.

Titration, it is called in the somatic experiencing world: a trauma healing principle that basically means less is more. Often trauma is a result of “too much, too fast” or “too little for too long”. In order to heal well in the long term, we have to move slowly, take breaks and add the hard stuff little bits at a time so that our bodies can learn to shed their protective layers as they are ready. We can learn to lay down arms when we aren’t under attack all of the time. We may do this naturally to survive, it turns out.

I noticed the urge to run, move quickly into doing, or acting on the “shoulds”: I should try to work out today, I should get on that zoom call, etc. I would take a moment to pause and check in. Usually this is when the tears would flow or the anger would burst. This pausing was a practice of asking my autopilot to take a backseat, and allowing my inner voice to drive. This pausing is medicine for grief in a world of go, go, go.

This collective pause is the antidote to Capitalism.

In a capitalist, white supremacist, patriarchal, sexist, heternormative, hegemonic culture, grief is a four (or five) letter word. It is often a “messy” and “tumultuous” experience that is rarely seen in the public eye. We give grieving people a window of time to heal and then we expect them to be back to work, to just “get over it”, to “be strong”, to not waste time crying, and most importantly, to keep your big feelings to yourself. We have lost a culture of grief circles, allowing our big feelings to be seen, held and honored by our communities. We have lost valuing grief as a portal into our capacity for love.

As humans, we have a lot to grieve. We carry the enslavement and exploitation of Black/African descended peoples, the genocide of Indigenous peoples, and the loss of connection to our earth, among so many other big hurts. If we can acknowledge and grieve our past, our pain and loss, we have a chance at breaking the cycle of trauma as it was passed on to us by our ancestors. We will also begin to heal the wounds of guilt, shame, and denial. Shedding all that keeps us from being present. So often when grief comes it brings all of our past hurts with it.

If we are lucky we get to grieve a little bit each day, mourning who we were yesterday, becoming closer to our essence, our true selves.

I am blessed, though sometimes I argue it feels like a curse, that I have somehow surrounded myself with friends who are all about feeling the feelings. With no booze or drugs to numb them out, feeling the big feelings has become somewhat of an erotic experience; an experience of aliveness. The deeper I felt pain, the deeper I could feel my capacity to love. My heart seemed to break open still more, and I would fall again, deeper into despair. Somewhere in there I would find compassion for myself, and then would come anger. Then the cycle would start all over again, in big and small waves, all day, all night long. A goddamn ocean of grief.

“Breathe, sometimes all that you can do is, breathe.” Lyrics from a song my ex taught me.

Many of us do not know how to show our big feelings, and thus we don’t know how to show up for other people’s big feelings. We fear we might be judged or worse, someone will try to fix us, not knowing they are leaving an imprint of shame on our already wounded self. Hence, the friends that stay at your side without trying to manage or fix your feelings become your lifeline, rare birds in a deserted concrete jungle.

Sometimes my grief felt very private, like a new relationship I’m not ready to introduce to my friends. It was quite convenient to grieve during a pandemic when isolation is applauded. However, there were also many moments when my body couldn’t hold all of it alone, and I found myself in the goodwill of those rare birds, sitting six feet apart in a park, in the dark, allowing my heart to break under the wing of their loving attention.

They let me fall into the abyss, to the darkest corners of my mind, and their presence allowed me to find my own way back out. One of the birds reminded me, “You know how to do this, you help others find their way all the time.” I felt into the okayness of the ground beneath me. It was just the tiniest bit more bearable than my thoughts. And then I remembered pendulation, a somatic experiencing phenomenon that allows you to resource your nervous system by moving back and forth between calm and activated states. I could tell my nervous system had me hostage so I asked the birds to show me a funny meme - thank God for the internet. I had enough flying for one night.

I could sense my nervous system begin to quiet after being with friends, even at a distance. I found my appetite came back when I was surrounded by loved ones. Being in nature also seemed to regulate my moods; the sounds of birds chirping is the reason I got up this morning, some days their song is also the reason to stay in bed. There is no straight line forward, grief is like a scatter plot: generally moving forward but all over the place.

I started to feel into my pleasure practice. It felt like pain. At first, I was met with resistance and self-hate. It was yelling obscenities like “Fuck off!” and breathing with a labored exhale. It was my fists pounding into the floor, full body crying, fantasizing about my ex, more full body crying, wanting to give up. Then, sometimes, an opening. A place I’ve never been before. A slow, tender me emerged and I touched myself with more grace and love than I have ever felt. I allowed my fingers to move wherever they wanted, with no destination. Where there is no force, there is pleasure. Breathe.

It’s taken me weeks to write this. My thoughts are finally beginning to clear. I didn’t write this for pity, help, or to tell you your situation could be worse. In fact, your situation could be worse, and my heart goes out to you. I hope you have support and that it gets better. I also hope you grieve any way you can - there is no right or wrong way to grieve, and nothing too small or big to feel the loss of. There is no moral in this story. No happy ending. My dream of being happily partnered and building a family and a community with a man I love is gone. For now. We have lost icons of our time, family members, and so many whose names will not be lost in vain. Now is the time to mourn the dreams, the loves, the lives, the memories. Eventually, on our own time, in our own way, let them go, and to one day start to dream again.

Maybe we will dream up new ways of grieving together, in distance and in closeness. I recently attended an online grief circle where the facilitator offered a keening: the action and embodiment of wailing in grief. It triggered the space to let the fullness of my grief be present. It taught me the sound of grief is just another song; the embodiment of grief is just another dance to be witnessed and given space.

Grief has become a friend. A place I have begun to discover my heart, what I truly love and what truly loves me back. The secret desires of my heart, body and spirit are being revealed. These desires, these dreams show up at the moment right where I want to give up, where I feel the most broken, ashamed, and weary. This is the gift of grief.